This is about the Arkansas-Missouri Railroad.

But first, Van Buren!

Van Buren lies just north over the river from the much larger city of Fort Smith. Van Buren is like Fort Smith's kid brother. Unfortunately, Fort Smith got into drugs and carousing and general raucous behavior, while Van Buren kept itself under a warm hat of responsibility and historical self-respect. What I'm trying to say is, its downtown is ever so much more beautiful than Fort Smith's, even though the latter town used to be some kind of breathtaking destination-town. For example, the above building (probably Van Buren's most famous) is an 1889 bank building that resulted from a feud between two bankers: since in the late 19th century the complexity and beauty of brickwork was indicative of a business's prosperity (and now you shouldn't be wondering why I am nostalgic for such times), one banker just up and built a bank right next to his rival's, only built his to be as architecturally marvelous as possible.

As it happened, none of it would really matter. Neither the "Crawford County Bank" nor the "Citizen's Bank"--the smaller of the two buildings, belonging to the other rival--managed to pull their business into the 21st century. Both of them (as well as the even older bank across the street) lost out to some bank buildings that probably didn't even use bricks.

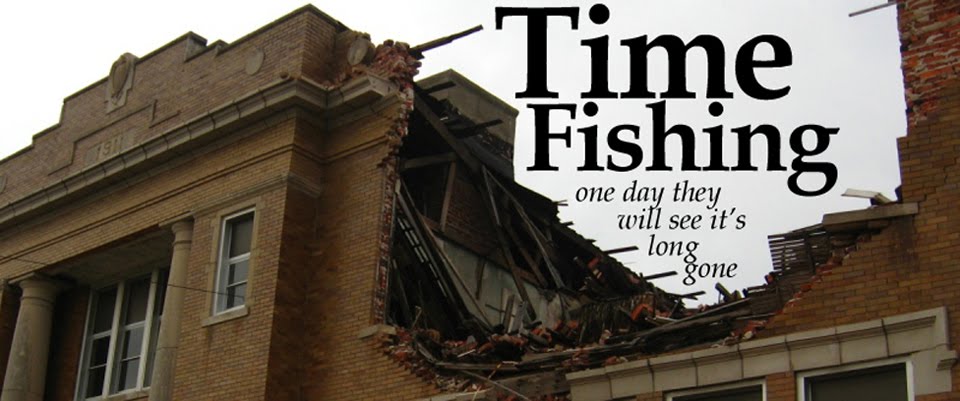

But in the end, Van Buren got to keep its built environment, and the Crawford County Bank now adorns all of the little "Visit Downtown Van Buren" brochures. Fort Smith, on the other hand:

They sacrifice their built environment so ten more people can park their cars on a Friday afternoon. Oh, sure, they left the pediment and some of the pilasters of this building so people (like me) can see them and just wonder what used to be there. The face remains, like the only piece of a shattered family heirloom we can't bear to throw away.

But let's get back to the matter at hand. Whatever railroad depots and tracks and excellent things Fort Smith had are long gone. Van Buren's, however, are not only still standing, but are still quite in use:

Yes, it's your average Italianate depot with the addition of a mission-style shingle setup, much the same as many of Arkansas's smaller towns', but the presence of a sizable crowd is what makes the difference. And what's that? That thing just to its right?

Ah yes. A train. The Arkansas-Missouri Railroad is a small, privately owned line operating out of western Arkansas and southern Missouri. Like the Maine Eastern Railroad, the Arkansas-Missouri operates a freight line as well as a passenger excursion line. They have a number of different excursion packages, stopping in little towns up and down the west edge of Arkansas. We could have chosen one with a seat in a caboose, or one with an acted-out train robbery (complete with blank-shooting pistols). We chose the one that went from Van Buren to Winslow and turned around. Not the most exciting, but take a look at the inside of the car:

It's vintage 1920s. The seats were springy, but did we care? The car is a relic of a time when care went into the making of everyday objects, transforming mundane environments into ones of beauty. Of course, a family trying to get from Little Rock to Memphis because their grandmother is about to die probably would not care if the car was just a steel box, and sure, anyone who sees the same beauty every day might forget it exists.

I wouldn't, though. The sublimity of the car and our surroundings transfixed the four of us (me, Jenna, Drew and Kelsey Spickes). The trip took us through little towns, shallow gullies, cages of blasted granite, pitch-black tunnels, deep gorges at the bottom of which lie the bones of the American telegraph network...

The conductor on our car was an old man, hard of hearing but full of stories. He told us about the train trips he would take in his early childhood on this same route, stopping at the tiny depots every town once had. Each station would only yield a person or two, if any, but one thing was guaranteed: the train would load bottles of milk from every depot. This was an image burned in his mind.

The little towns we chugged through weren't so notable except for an anecdote or two the conductors would relate here and there. Winslow was little more than an arbitrary place with an extra track to turn the train around. But one town I will always remember: Mountainburg. Here's why.

There are three towns in Arkansas that start with the word "Mountain." They are Mountain Home, Mountain View, and Mountainburg. Mountain Home is famous for being the Arkansan version of Florida: old people go there to pretend the rest of the world doesn't exist. Mountain View is famous for attracting musicians from not just around the state, but from around the country, and for just being all around one of the best towns ever. Mountainburg is famous for dinosaurs.

Yep. When we passed the dust-mote sized hamlet, our conductor told us what he used to tell passengers about Mountainburg: "I used to say it was the only place in Arkansas you'd find dinosaurs," he said. "Then I found out about this place up north that has 'em too." Well, the "place up north" is, of course, the late Dinosaur World, but that's too tangential to go into now.

Mountainburg has two dinosaurs. Click here to see what they look like. We could just make them out from the window of our car, and that little glimpse made my day. Of course, the train had already made my day four or five times over, but hey, you know.

Seems like I need to wrap this story up. The funny thing is, I actually enjoyed this train trip more than the one in Maine. Something about the scenery, the antique car, the food, the conductors...it was just better. One more leisure railroad remains for me to encounter in Arkansas, and my ultimate goal still stands: ride a steam locomotive. All in years to come. Don't touch that dial.

In the meantime, I bid farewell to 2009. It has been a good year for Time Fishing. Maybe not so consistent, but good nonetheless. I look forward to fishing in 2010...

-Jonesy

P.S. Take a look here to see pictures of dinosaur statues all over the country. This is awesome.