"All across America, hamlets grew into towns, and towns into cities, with the coming of the railroad; and with the going of the railroad, cities faded into towns, towns into hamlets, and hamlets into ruins. As if it were a vessel supplying blood to the brain, the shutting off of the railroad brings on stroke, paralysis, and death..."

--Donald Harrington, Let Us Build Us a City

But the real blood flow in these towns and cities wasn't actually engines, cars, or cabooses: it was people. And the blood, the people, would exit and enter the railroad cars into the bloodstream of America by way of depots. I've been here before--to train stations--and I've returned again. The first few are all remarkably similar to each other, and all three are conspicuously located along U.S. Highway 64 (a new, rerouted vein).

Russellville's depot stands proud on a podium of pristine concrete, surrounded by curving sidewalks and pedestrian statues crystallized in bronze. It's the center of attention in a downtown restoration not, hopefully, just limited to Russellville. The station, like the other two on 64, still commands its own section of tracks, but no passengers have boarded a train from this station in probably 50 years.

Continuing to the west, Morrilton (the aboriginal location of Harding University) wields a dusky downtown and another Italianate station, this one converted into a geneology museum. The station, like Russellville's, owns its own little section of sidewalk with brick borders and immobile wooden benches. Do festive Morriltonians inhabit these benches at any time? During our short stay in the town (near twilight), we spied no pedestrians.

The last stop on highway 64 is Atkins. Though Atkins' station is quite similar to the other two, it has been left high and dry on a slough of gravel and weeds, separated from its blood vessel by a rude wire fence. The station does not seem to be home to any organization in particular, but it does bear the town's name and appears to be in generous upkeep.

In a different direction, in the north part of Arkansas, south of Harrison and north of Conway, we find a true railroad hamlet: Leslie.

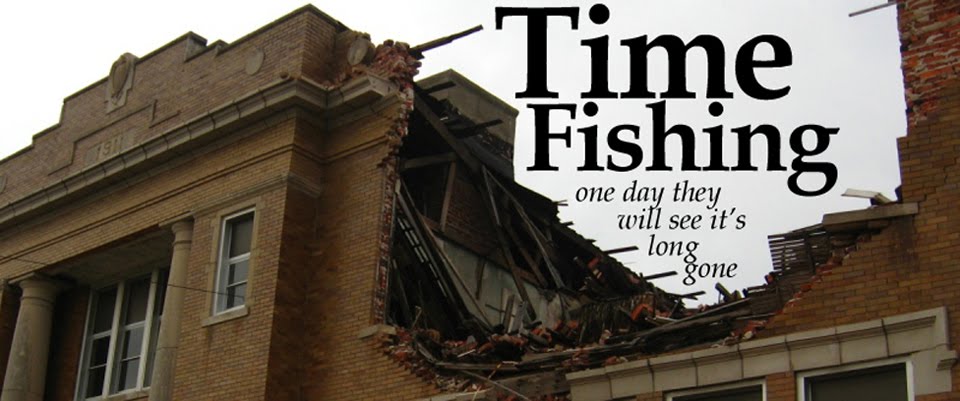

Even in 1950, the town's depot was forlorn and probably mostly empty of red blood cells. Leslie was legitimately a town that was born and died with the railroad; in the early 20th century, it was the end of the line, with only steeper grades reaching northwest beyond. Its population doubled and redoubled and re-redoubled until it teemed at nearly 10,000, a gurgling mass of industry, entrepreneurs, and--no doubt--gallons of hard liquor. But the industry left with the railroad, and the population finally tumbled down to around 500 today.

I had to blink and rub my eyes a couple of times before I decided that yes, this was a train station, and yes, trains once did chug their way this far into the mountains. But they do not anymore, and Leslie's depot is now embargoed into the property of a local lumber company. Stripped of its passengers, its rails, and its dignity, the building probably does its best to hide its original, all-important identity.

Leslie's is not a story of failure, however. The little town is just off the beaten (automobile) track towards Harrison and Eureka Springs, and has managed to save their downtown from desolation, instead transforming it into a pleasant, antique-store laden diversion. It's also home to a few cafes and a renowned privately-owned bakery.

Each of these towns with their stations reminds me of a time when cars did not own our lives, and gives me a little (just a little) hope that one day we may pluck them from the hands of the lumber yards and historical societies and cobwebs to supply that energizing lifeblood again.

-Jonesy

No comments:

Post a Comment