This is the one transportation-related thing that I hate more than automobiles.

Then:

Automobile transportation took place on regular highways. They are the roads that we now consider to be the "back roads," the ones that go through actual towns. Trips took much longer by car, but were full of character as towns were full of commerce, people and life.

If you wanted a more direct route, you could just take a train. Intercity routes were all-inclusive. Towns that railroads didn't reach were scarce. Even the most minuscule of hamlets usually had their own stop. Trains in the 1930s, 40s and 50s were sometimes even faster than the modern Amtrak routes because of better tracks, less competition with freight lines and more right-of-ways.

Now:

It's possible to take your car and drive it across a country apparently made up of absolutely nothing except for rest stops, bill boards and the occasional cluster of high rises. To most drivers, towns along the interstate are exactly as valuable as their selection of fast food. Cities invited the interstates in with open arms, then found out that the highways did nothing but spread them paper-thin, eviscerate neighborhoods with depressing concrete vistas and create garbage-strewn wastelands where streets and boroughs once stood.

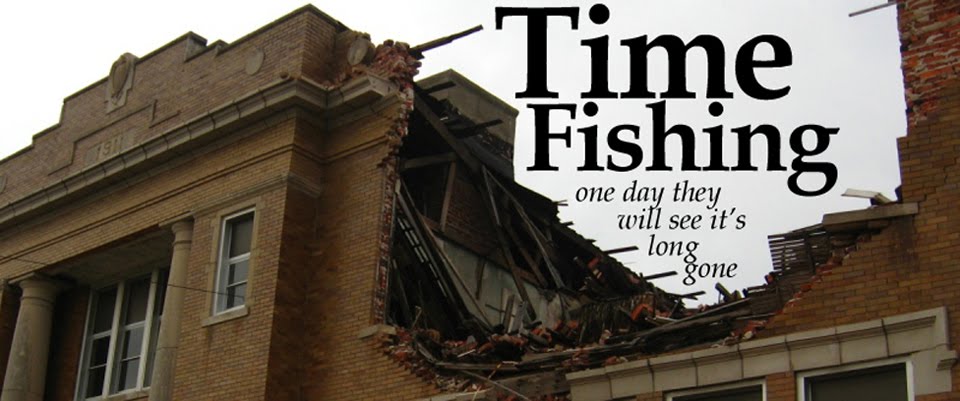

Pictured: Madness

The biggest problem comes from how cities decided to incorporate the highways. Instead of treating them like airports, letting them flow alongside cities at a safe distance, they let them come right in through the city center, dissecting them in

Additionally, all of the once-flourishing and personality-laden businesses along the old highways died and are still rotting there. This was inevitable. I would much rather visit a kitchy wigwam motel than any one of the cookie-cutter La Quintas clogging the country.

Sure, interstates are ultra-efficient and marvels of engineering. But that doesn't stop them from being dehumanizing.

Future:

People hate driving for hours and hours. They really do. So this is one area in which, I feel, a slight glimmer of hope can be seen through the cloverleaf intersections. Intercity public transit may make reappearance in my lifetime. Obama relegated a cool $8 billion towards high-speed trains a year or so ago, moving him up a notch in my book.

Then again, China is planning on spending something like $300 billion to amp up their already-nice railroads and highway people want to relegate $600 billion in Arkansas alone. So...damn, I guess.

5. Apparel

Again, another item that boils down to aesthetics. But I feel it goes deeper than that.

Then:

While in public, men wore suits and hats. End of story. Suits had great variety of color, style and decor and were tailor-made by clothiers. But this is the most important bit: Everyone wore clothing that complemented the human body. Even the poor and homeless looked distinguished--maybe not to the eyes of the time, but to our modern eyes they do. Also, no such things as t-shirts (which I wear, by the way).

Whenever I watch a movie made in the 1950s or earlier, my overwhelming feeling is always, "Why can't we dress like this anymore?"

Now:

Everything resembling a dress code has been obliterated, its remains trampled on and left to putrefy. Suits are a necessary evil: We wear them to work, but only if we absolutely need to and definitely not on Fridays. All other times, we basically parade around in our underwear. We buy ready-made clothes from department stores who outsource almost entirely to sweatshops in third-world countries. Crocs, flip-flops, jorts, oversized t-shirts, sneakers--the lot of it.

See, I think dressing well purports a certain attitude of respect, not just for others, but for yourself. When you dress in a way that complements you, you automatically feel better about yourself. And when everybody does, it elevates the respect you have for your fellow man. It improves communication. And going back to the tailoring, think about how special it is to own a suit that was made in your town by someone you know. Who can say that anymore?

However, I will admit that apparel is overall easier for women now. Even though I still believe people--including women--dressed better in older times, I know that clothes were more restrictive for females. It still is, sometimes, but it's less complicated.

Future:

We absolutely will not go back to old ways. The overall cultural revolution of the 1960s and 70s put the dress codes so far behind us that I will eat my shorts if the masses ever want to go back to them. While I'm thinking, "I wish I could dress like that," most everyone else is thinking, "I'm glad we don't have to wear suits all the time anymore." It's just so easy to slap on a shirt, shorts and flip-flops that dressing well seems too old-fashioned to exist.

4. Big Box Commerce

Then:

All business, big and small, took place downtown. The downtown was a strictly organized sector that allowed for a mixture of business, pleasure, and residence--folks met in stores owned by their fellow citizens and sometimes lived above them in loft apartments. Many town shops were what we call the "third place," a midway between home and work that friends and acquaintances frequented.

Buildings were built for multiple uses and when they changed hands, new stores could easily be built within the confines of the old walls. Cars were allowed within the space of downtown, but the champion of its borders were pedestrians: everything was within walking distance.

Many products were house-made or unique to the environment of the town. Tailors, soda shops, drugstores, banks, cafes, movie theaters, even churches and civic buildings were all located in one area.

Now:

Wal-Mart. Home Depot. Walgreen's. Starbucks. McDonalds. Malls. The list goes on. We've put our trust in these supermassive companies that we now call "big box retail," and I don't really need to explain what they are, because they are in every town.

But the whole idea might be best explained by talking about Wal-Mart, the most recognizable of the giants. Sam Walton's plan was to build these so-called "discount cities" (the original subtitle for Wal-Mart stores) on the edge of town, far away from the original business sectors. He probably didn't intend to actually replace them entirely, but that's what ended up happening.

Through the 60s, 70s and 80s, these huge franchises with the "slightly out-of-town" model got bigger and bigger and bigger until now most towns have two distinct areas.

Let's take Searcy, for example. Here, the original business district is on the west end of Race Street and the big-box part is on the east end. Where we see Wal-Mart (note: at the very edge of town) and Chili's and Fred's and so on used to be mostly wilderness between Searcy and Kensett. Now, it's a different kind of wilderness.

The third place is dead and gone. People don't congregate in places like Wal-Mart to socialize, because there's no trace of locality. You could go to Cabot and it's exactly the same as the big boxes in Searcy. It doesn't matter where you are, the big boxes are exactly the same. And when a big box dies, its hulk sits there, rotting, usually until some other big box tears it town to replace it with its own cookie-cutter standards.

There's nothing for pedestrians. Walking between the big box stores is usually not just dangerous, but downright impossible. Zoning standards demands these huge drainage ditches that are uncrossable by pedestrians. So we drive everywhere, and that aspect of community is further degraded. And this all ties into a much, much larger issue that I'll deal with further down the line.

And what about downtown? Well, up until a few years ago Searcy's original business district was certifiably dead. The few stragglers that made it past the 60s and 70s bubbled into rambling masses: First Security Bank now owns a full block of downtown and has offices in an entire row of storefronts that were once separate shops; Sowell's Furniture owns almost all of its part of its end of Arch Street. We're just now starting to see a resurgence of interest in the area, but we have to fight for it. And it's a long, uphill battle.

Future:

If we see a transportation overhaul and the replacement of gasoline with something else, big box retail will collapse on itself like the huge package of hot air that it is. But we have to fundamentally change first.

3. Architecture

Throughout my time as an art student, and especially after visiting the architectural mecca called Chicago, I've eventually concluded that my very favorite form of art is architecture. Maybe it's because it has the ability to transform entire living spaces into works of art and alter our perception of the world as we know it like no other art form can.

Then:

Every town, even the smallest, built their environments to last with a variety of very different, but compatible, architectural styles. Neoclassical, Victorian, Gothic, craftsman and even art deco were able to coexist in a way that complemented each other in increasingly rewarding ways.

Now:

Modern architecture happened. Its tendrils were creeping around in the big artistic minds even since 1900, but the true fruits of the various movements weren't really seen stateside until after 1950.

The Bauhaus, blobitecture, De Stijl, functionalism and the very worst, brutalism, all reared their unsympathetic heads and took over the majority of architectural firms.

Now, modernism as a whole emerged as sort of an evolution of all other styles, and I suppose on paper it might work in the minds of those who understand the principles behind each movement. But that's exactly the problem. Architecture, above all other art forms, is specifically for the public. It's not like you can design a town and display it in a gallery, then take it all down after too few people show up.

See, none of these new forms mesh with the older, traditional forms at all. They stick out like the proverbial sore thumbs, degrade their surroundings, and above all, alienate people. They appeal only to the very high-minded sort who came up with the styles in the first place. And with them came an acute disdain for traditional styles, which seemed only to propel the new styles toward clashing as violently as possible with their older brethren.

That all might not have mattered if the styles didn't trickle down to major manufacturers. As it turns out, most modernist styles are cheaper and easier to produce than the the older ones, and that means builders don't care to look in any other direction. Now, when the oldest and most beautiful structures are torn down, they are frequently replaced with something that is lacking entirely of grandeur, warmth or subtlety.

Take Penn Station, for example. Built in 1910, the station was one of the Pennsylvania Railroad's palatial terminals in Manhattan. Here's what the interior looked like:

Tremendous, vaulted ceilings, Corinthian columns, a space fit for the most grand of cathedrals. Arriving into Penn Station, a traveler must have felt like he or she was part of something truly great. You were arriving, like royalty, into a vast castle of the greatest city on Earth.

On account of progress and the atrophy of America's passenger railroads, the entire thing was razed, to literally everyone's horror, in 1964. A new terminal, still referred to by its name, was erected in its place. Here's what it looks like now.

Low ceilings, diffused fluorescent lighting, Styrofoam ceiling panels. Practical, but with all the visual appeal of a dumpster. Arriving in the modern Penn Station, a traveler feels the stress of the voyage and will mostly likely reflect on the meaninglessness of his or her short, brutish life. Or else they just won't notice the building at all.

This sort of things happens everywhere, all the time. The grand and artistic structures of yesteryear are razed to make way for parking lots, or at least structures that might as well be parking lots. In short, our cities have been raped and left in ditches.

Oh, and big box stores are all ugly and modern. Just thought I would throw that in there too.

Future:

Some virtuous people are in the business of saving old buildings, but it seems that for every beautiful thing saved, ten more are broken down. It just doesn't seem fair to me. I have been to a few cities where the built environment is treated with respect, and when old buildings are burned or razed, the new ones are constructed in a way that conforms or complements the rest of the city. But they are rare.

The simple fact that modern architecture exists and is practical simply defeats any reason for traditional styles to be used. People in this country just don't care if a building is one year old or one hundred years old, if a profit might come from demolition and replacement.

Continued in part three.

-Jonesy

No comments:

Post a Comment